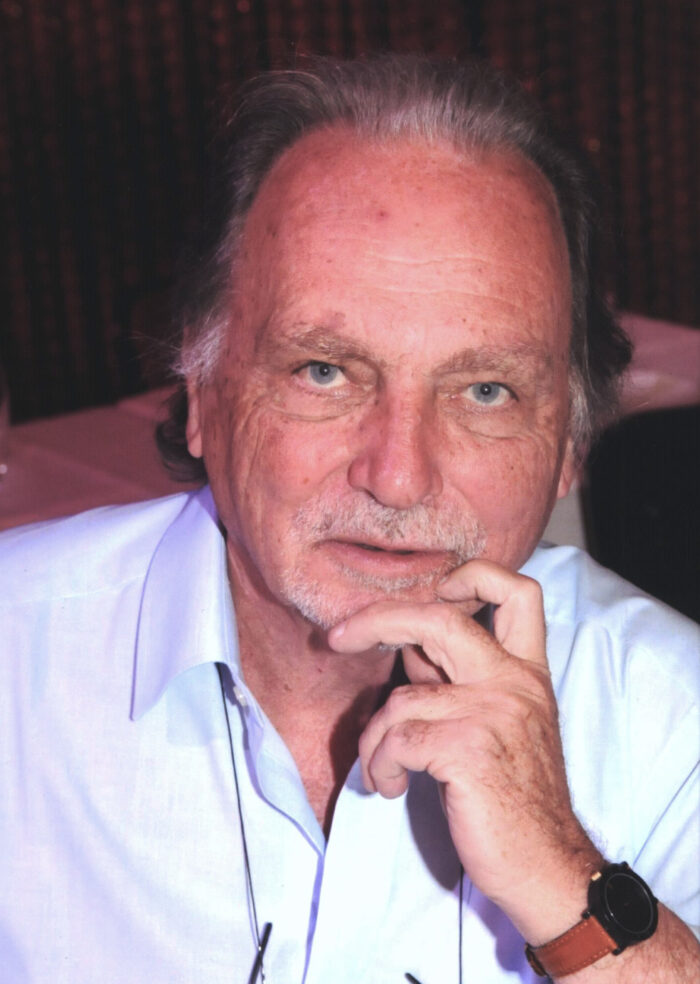

A conversation with Arch. Gonçalo Byrne

A conversation with Arch. Gonçalo Byrne

'I compare the projects, a little, to what happens to children: after a certain point they have their autonomy, their life...'

It was still as a teenager that you decided you wanted to be an architect. What did architecture have, and still has, that was irresistible?

The option of doing architecture, in my case, was relatively premature. From the 3rd grade, which was equivalent to the 7th grade nowadays, it was clear to me that I was interested in architecture. My father and brother were engineers but architecture has the artistic component that I like. Still in elementary school, I was lucky to have an excellent drawing teacher in Canas de Senhorim. One of those school teachers who still existed in the late 1940s, an excellent teacher, very austere, who punished, but who was a reference to me. On weekends, as I liked drawing so much, he taught me at his home. Then, in the 3rd grade, I met an architect in Leiria, Camilo Korrodi – son of a very famous architect, Ernesto Korrodi, still a reference today – who had a studio that I thought was fantastic. Then, on a high school vacation, I returned to Urgeiriça by bus and an American writer sat beside me. He asked me what I wanted to do and I said that I liked architecture. The guy immediately recommended me to read a book about the history of a famous American architect. Finding an American book, at that time, was complicated but I had to come to Lisbon, months later, and I found it. That further reinforced my decision. Fortunately I did not regret it and, even today, I really like this and I hope to be a strong contestant of the retirement.

You have a passion for cities. What is the city that most impresses and inspires you, architecturally speaking?

I usually say that all cities are fantastic, but I think that in all of them there is a little bit of Lisbon. It’s a pity that it has a historic center falling apart. In Portugal, there is no city that does not have serious abandonment problems in historic centers, but Lisbon is capable of being the worst. Although there are efforts. I think that the current management of the Câmara de Lisboa, after many years, has well-structured projects, namely the city planning councilor. I do not understand why there was never a person of such caliber in the management of the Chamber. Finally, it exists and I wish him to remain there because, in a city, these policies are either developed over a long period of time or are of no use. There must be continuity and convergence of political will around quality projects and this is happening in Lisbon, right now. The problem of the Baixa recovery is an economic problem. Most landlords, those who still have tenants, are poorer than the tenants themselves. So there are no renewal mechanisms. In spite of this, investors know that, in a while, those plots will be worth a lot of money and it is preferable to do nothing, because over time the capital of the plot values. There are a number of phenomena that have contributed to that. There must be a financial restructuring of the entire Baixa. And that perspective exists, finally, thanks to this plan.

You once said that “a project must be able to make you feel that it has always existed”. What do you do for your work to achieve a perfect fusion with the place where it is inserted?

In these things there is no recipe… if there were, the projects would all be the same and would not be that funny. What is fascinating about architecture is that each project is a challenge, which basically presupposes two things: great rigor and demand, on the one hand and, on the other, a fascination, a taste, a commitment… to dive into the terrain. The worst thing that can happen is a project made by default. It will certainly give a bad building. Buildings don’t lie. A person who has a minimal understanding of architecture realizes, when looking at a building, the process that was behind it. There is another thing that is very important: cities have long times. In Portugal, the main cities have about two thousand years of History. So there is always a problem that is the relationship between what exists and what is projected. And I think it is very important to understand, in depth, what was done before our project. But cities, despite having this heritage and memory, are living organisms and must continue to live, which means that their identity must be reinvented and therefore projects always have a transformative, creative dimension. People often think that cities should be untouchable, one should only repeat what existed, but that is the worst thing you can do to a city, because it makes it a museum. This is killing the city. Unfortunately, this is what is happening in Portuguese cities, not by direct action, but by inaction. The worst thing that can happen is that buildings lose use, start to be uninhabited, abandoned, because they immediately and inexorably enter a process of ruin and this precipitates the erosion of cities.

Is it easy to disconnect from the work once it is finished?

There are many colleagues of mine who are obsessed with the misuse of the work. But there is one thing that is important: the works go beyond architects. It is completely unrealistic to think that I will continue to rule the work all my life. Firstly, it is not mine, and secondly, I hope it can fulfill one of the characteristics of architecture, which is permanence in time. You will have to stand alone. When I finish a work it is clear that I am more or less attentive but I think it has to be mature. The work, when delivered, when it will live its life with its owners, must be autonomous. It does not make much impression on me, once finished, that the work goes on by itself. Who knows if, one day, it is unable to support itself and someone decides to demolish it. It is a condition of the buildings’ own life. I compare the projects, a little, with what happens to children: after a certain point they have their autonomy, their life. It is not exactly the same because buildings do not have a closed cycle, like organic life. If there is a building from 1800 that is now inhabited, it is because it has been rehabilitated, readjusted to today’s models of life. So a building can perfectly live forever. But that is not just in the hands of the project, it is enough to have, for example, an earthquake like this one in Japan [Tohoku earthquake, March 2011]. But worse than natural catastrophes are those that are projected by man; war can devastate a city, or the worst of all , which is abandonment. A city may end up in an archeology camp, like Conímbriga [Roman city near Coimbra], which has been totally abandoned and has disappeared.

This interview is part of the Artes & Letras Magazine # 19, April 2011

Partially automatic translation from portuguese: some expressions may differ from their actual meaning.

News & Interviews

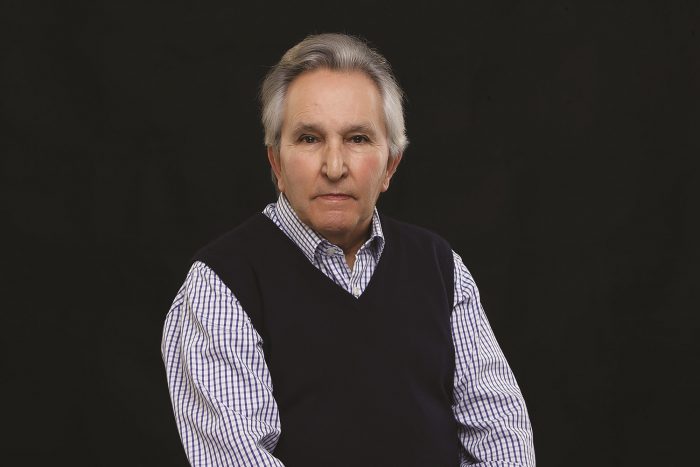

A conversation with Eng. Guilherme Pinho e Silva

'Brisa focuses on people. We seek to innovate in new technologies and methodologies. I am responsible for the efficient management of assets in order to achieve the objectives in a sustainable way. ’ Read more

A conversation with Arch. Pedro Ferreira Pinto

'I am looking for an architecture with a minimalist aspect and without excesses of austerity that tries to respond to society's challenges. I try to introduce an idea of simplicity, elegance and culture. ’ Read more

Talking about Eng. António Rocha Cabral

This year will be marked by António Rocha Cabral's farewell and we couldn't help but pay tribute to him. In this interview, Maria do Carmo Viera tells us about Mr. Cabral, undeniably one of BETAR's most important figures. Read more