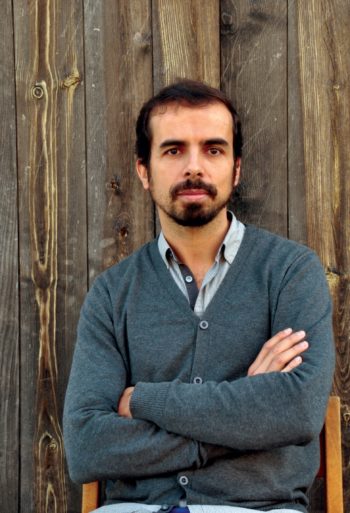

A conversation with Arch. Carlos Ribas

A conversation with Arch. Carlos Ribas

'The principles of sustainability have always been those of landscape architecture [...] The national circumstance of having "specialist" professions that understand nothing about the territory means that we have a growing dehumanization of the landscape and a very strong dynamic of unsustainability'

Tell us about your academic and professional career and why you chose Landscape Architecture.

My path is very simple. My choice was motivated by the desire to intervene in the territory, to build the landscape (with work), instead of studying-observing-describing-interpreting without the consequent pragmatic action. I confess that I was also fascinated (and still am) by the Instituto Superior de Agronomia and Tapada da Ajuda. The landscape architecture course, which celebrates its 80th anniversary this year, was undergoing a profound transformation at the time, with the restructuring of the syllabus and the non-renewal of contracts with the old landscape masters. Being in the midst of this change was turbulent, but we got around the disappointment with studio work (from the 3rd year onwards). That, at Proap, with João Nunes, was my real academic and professional training. I continued every step of my career at Proap, of which I was managing partner between 2001 and 2014, until I left in 2015. Since then, I’ve returned to the national market and to landscape architecture design work, in all its scopes and scales – from public works to private clients; from the micro-patio to intervention on a territorial scale. Working at all scales and the relationship between them are the cornerstones of landscape architecture.

What is your definition of architecture and landscape architect?

It is the architecture of the exterior space in its total scope, of the systemic intervention in the physical space with the technical-scientific and cultural awareness of all the variables in equation and, since its inception, with a markedly humanist mission and an ecological approach “ahead of time”. The principles of sustainability, now universally enunciated by everyone, have always been the principles of landscape architecture. When I talk about the profession, I show an image of a primitive man as the first landscape architect: reading the natural space to choose a place to settle, ensuring safety and comfort, availability of water and food, and what would already be an unperceived sensitivity to feel the beauty of places, was the work of a landscape architect. In some countries, the landscape architect intervenes upstream of any transformation process to study the site and determine the form of occupation. The absence of this stage and the (growing) national circumstance of having “specialist” professions that have no understanding of the territory means that we have a growing dehumanization of the landscape and a very strong dynamic of unsustainability. Being a landscape architect is one of the best jobs in the world, due to the continuous discovery of new sites and production of works that are very relevant to those who use them. It’s one of the worst jobs when we’re faced with situations of blatant institutional disregard (it’s all too common for an elected official to decide, unilaterally and on site, to make alterations or deletions as if it were perfectly natural) and when we’re navigating an environment in which landscape architecture is not highly valued.

You have participated in some remarkable projects and in a conference on the importance of water in design. Would you like to talk about some of the challenges?

I would highlight EXPO’98 because it was a national process, with truly international demands and, therefore, a huge challenge, a great learning opportunity and a sense of collective pride. Taking part was an irreplaceable experience. Proap tendered for the Tagus and Trancão Park project, a metropolitan, riverside park, in association with a major Californian studio, Hargreaves Associates. Winning the competition resulted in a project of enormous complexity and, for us, absolute novelty. My participation in the conference ended up focusing on the discussion of Lisbon’s General Drainage Plan. I talked about multiple concerted interventions such as the construction of retention basins, the transformation of flat roofs into green roofs, intervention in the surfaces of streets and squares to make them capable of retaining flow, rather than quickly repelling precipitation, etc. In city management, water must appear as the generator/guide of “design” and the guidelines for specific interventions must correspond to large-scale strategic objectives. The resolution of flooding in Lisbon will have to involve a General Water Plan for Lisbon, the strategic integration of “water” and “sewage”, which the master landscaper Gonçalo Ribeiro Telles advocated for decades.

You’ve taught at several universities. What do you get out of teaching? And what do you want for the future?

Teaching always forces us to study more, to systematically question what we have done, to try to unambiguously support what we are affirmatively trying to teach, to be confronted with reasoning and spontaneity that is effectively “clean” and often surprising. That’s why, when we truly dedicate ourselves to these teaching opportunities, we always come out of them better technicians and better people. I have many well-defined goals, but one of them is to be able to continue collaborating with my friends at BETAR.

This interview is part of Artes & Letras Magazine #146, November 2022

Partially automatic translation from portuguese: some expressions may differ from their actual meaning.

News & Interviews

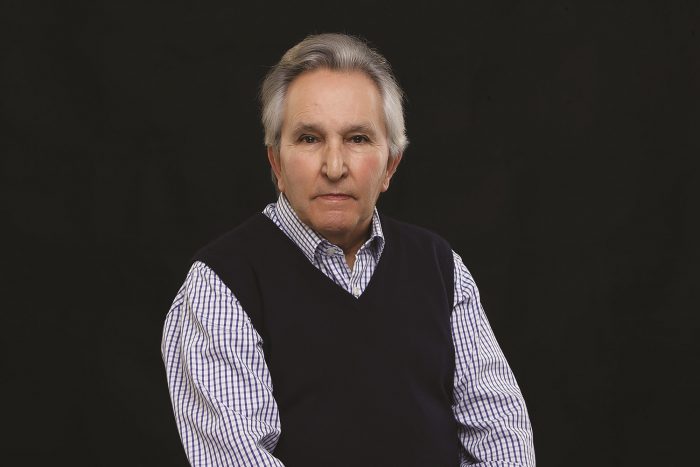

A conversation with Eng. Guilherme Duarte

'My desire is to stay in Africa because contributing to this structural change is priceless. It is not about telling the story, but being part of it.' Read more

A conversation with Arch. Paulo Pereira

'It would be very important for the landscape architect to be heard properly and the idea that he only comes to "add the flowers" later, must disappear' Read more

Talking about Eng. António Rocha Cabral

This year will be marked by António Rocha Cabral's farewell and we couldn't help but pay tribute to him. In this interview, Maria do Carmo Viera tells us about Mr. Cabral, undeniably one of BETAR's most important figures. Read more